Part 19 - Emily Ralph

How did the use of images influence the Victorian reader? What can be gleaned from not only investigating individual texts, but viewing them as an exhibit that was intended to be viewed alongside other published work in a periodical? Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone was published simultaneously in two periodicals, Harper’s Weekly and All the Year Round. Though there is plenty to analyze within the text itself, as Linda Hughes states;

“Insofar as printed texts initiated and sustained a pervasive dialogism—ideological, political, visual, aesthetic, and commercial—they more closely resembled an interconnected web of discourse than a city. The web or network is a particularly resonant metaphor given that remediated Victorian print is increasingly accessed via the Internet. Victorians themselves also glimpsed print culture in these terms” (3)

By viewing The Moonstone not as a standalone text, but rather as a strand of a vast and interconnected web, it seems that two distinct narratives emerge, especially evident in their treatment of Miss Class in the nineteenth instalment of the novel. By pairing the instalment with sympathetic or antagonistic works, the magazines are able to shift the cultural dialect in which The Moonstone communicates to us.

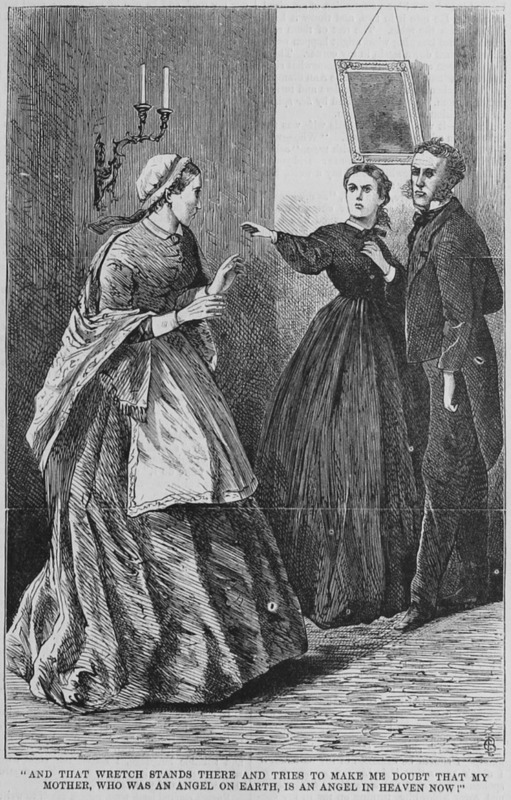

The nineteenth instalment of The Moonstone explores religion and the redemption of women through the eyes of Miss Clack, but the large plate in the centre of the first page of the instalment provides a change of perspective and allows a more nuanced and critical interpretation of the events which occur at the Ablewhite’s household. The images which appeared in Harper’s Weekly Magazine that were specifically meant to accompany their chapter of the moonstone always appeared on the first page of the story, and given that in many cases the images would present the most compelling point of the chapter, they influence the sympathies of readers before they even begin to read the instalment. By placing Rachel in her black mourning dress (with Drusilla Clack evidently not in the correct funerary colours) and backed by Mr. Bruff, Miss Clack is immediately placed in the part of the villain. The caption below the image serves to give the readers context for what exactly has occurred to cause Rachel to turn so completely, and we are left aghast by Clack’s insensitivity before even reaching that scene. The character of Clack herself in the novel already serves to poise some very critical questions to the proselytizing nature of Christianity in the novel, especially when it comes to tragedy being taken advantage of as a means of conversion. Throughout the chapter, Clack disparagingly refers to “the fallen nature in Rachel”, and her “hideous, worldly hardness” that come as a result of her grief and which she references “the mother” as the cause of, which the illustration provides us reason to take in a much more negative light than that of a well-intentioned woman who simply doesn’t know any better (Collins 249, 255). This is not the only instance in the publication which seems to prioritize motherliness over godliness.

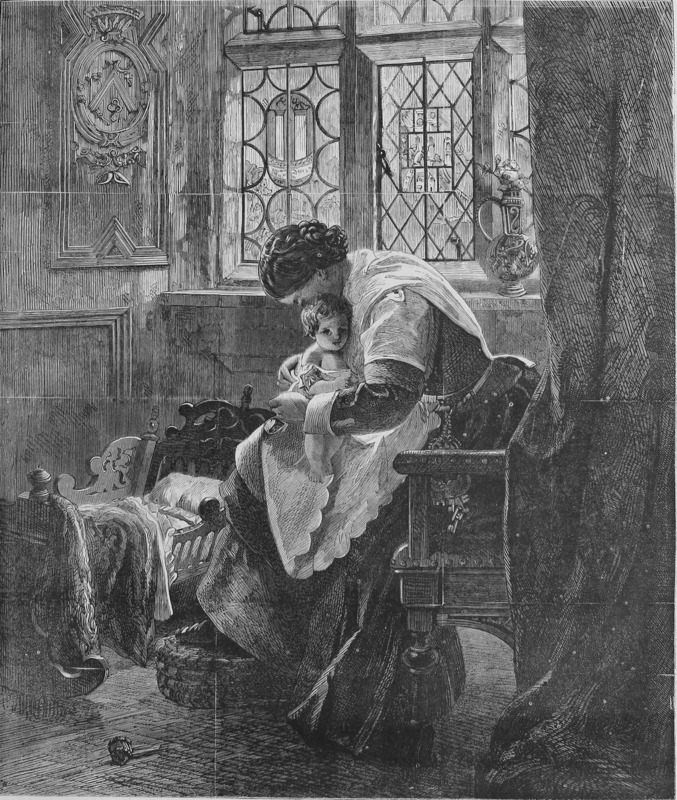

The front page of the Harper’s publication depicts a woman cradling a child, and though the exact relationship between the woman and child isn’t clear, it’s an elevation of the importance and beauty of motherhood which influences the reader’s thoughts before they even reach the section on The Moonstone. The plate on the front cover, titled “DRESSING BABY”, is a deceptively simple composition depicting the mother and child against a relatively mundane domestic backdrop. However, there are visual cues which politicize the image, especially through the context of The Moonstone. Through placing the ornate glass windows behind the woman, it creates the same ambience of the stained glass windows of a church in a secular setting. The motif of mother and child also eludes to Mary and Jesus, further strengthening this religious correlation. Through creating religious undertones in an entirely secular image of a mother and child, it applies a religious reverence to the image. Though something like that could be considered idolatry, in an issue that contains such a sensitive piece of writing about how religion and religious fervour can negatively impact the grieving of a mother by painting her as an imperfect christian, this serves to create an image of the mother as an angel. This angelic mother is something that, throughout the chapter, Miss Clack refuses to or simply is incapable of conceptualizing. However, this image proves that just because the narrator is unable to conceive of a goodness that does not rely upon a fear of God for its existence, it is still something very real. However, the issue of Harper’s delves even further into religious skepticism in some of the other creative writing published in its pages.

A poem titled “ON GOING TO CHURCH” also appears in this issue, which serves not to provide a counterargument to a character like Miss Clack, but rather, to ridicule her. Published in the section “Humors of the Day”, the poem lists several reasons why people might go to church: “For a walk […], for speculation […] to meet a lover […]” just to name a few, and concluding by stating that “few go there to worship god” (Harper’s 299). By listing the great many reasons why people go to church and then explicitly stating that almost none of the people who attend actually intend to worship, the piece digs not only at the average church goer, but also at fanatics for being the few who don’t understand that the church is, at its core, a gathering place for the common people and not one for fire and brimstone, regardless of what the bible says it should be. Though the poem is clearly satirical based on its tone and the section it’s placed in, it pokes fun at both groups, but more so at the final mentioned one for having the presumed gall to think that their own ideologies own the space of the church. By placing this after The Moonstone, it seems to make a direct attack on Miss Clack, who intrudes on a family trying to grieve, gossip, and make and break off engagements. She makes everything worse by trying to convert everyone, and as such, she is ostracized from the group, just the same as the group at the end of the poem is othered. This said, Dickens’ All the Year Round takes a much softer stance on Clack and religion as a whole, seemingly more sympathetic to her cause.

All the Year Round provides more stories that compliment than contrast Clack’s worldview, creating the impression of a more sympathetic version of Clack’s narrative than that presented in Harper’s. In particular, it gives quite a lot of space in the journal to an account of the inhabitants of the Pacific Islands, commentating on their lack of civilization and encouraging their conversion to faith. All the Year Round is an altogether sparser volume, comprising of longer texts and no images to speak of. The lack of images forces readers to actually read the text to make their assumptions, and it also places The Moonstone first in the issue, meaning that there is little to influence opinion before reading the story. The same, however cannot be said for after the story, in which certain facets of Clack’s perspective seem to be confirmed. By stating that “it is to be hoped that the Anglo-Saxon hand will make its mark felt before any other can take its place.” And referring approvingly to “the followers of the prophet” attempting to convert the inhabitants to “the true faith” with “whips and rods”, it seems that an ideology very similar to Miss Clacks is being applauded in a colonial form (Dickens 513). Miss Clack embodies the very ideologies of conversion above all else and sees Rachel and her family and friends as uncivilized, making the connection very easy to draw. By painting it in such a positive light, it serves to reinforce positive opinions of Clack’s behaviour, and question negative ones or at least paint her intentions as well meaning (if her execution itself was flawed). In this sense, All the Year Round seems far more forgiving of Clack than Harper’s is.

It’s incredibly clear that through the use of the different narratives that frame The Moonstone, the narrative can shift wildly from deeply sympathetic toward characters to mocking them. By looking at The Moonstone through the lens of the texts it was originally printed alongside, it allows new narratives to emerge, narratives that suggest that Collins was perhaps not in full control of the narratives he wrote given how vastly they differ from magazine to magazine in spite of the written words remaining the same. Though most of these fascinating images and accompanying tales are lost to todays readers, they provide valuable insights into how the print world shaped Victorian culture, and how advancements such as the internet and social media might be functioning in similar ways today.

Works Cited

Allingham, Philip V. “The Harper’s Weekly Illustrations of The Moonstone (1868-1951).” Victorian Web,

Victorian Web Foundation, 25 Aug. 2016, victorianweb.org/art/illustration/jewett/intro.html.

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Edited by Francis O’Gorman, Oxford University Press, USA, 2019.

Hughes, Linda K. “SIDEWAYS!: Navigating the Material(Ity) of Print Culture.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 47, no. 1, 2014, pp. 1–30, https://doi.org/10.1353/vpr.2014.0011.

"IN THE INDIAN ARCHIPELAGO." All the Year Round, vol. 19, no. 472, 1868, pp. 513-517. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-periodicals%2Findian-archipelago%2Fdocview%2F7832048%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D9838.

Harper's Weekly, 9 May 1868. American Historical Periodicals from the American Antiquarian Society, link-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/apps/doc/QDAMFH819315120/AAHP?u=ucalgary&sid=bookmark-AAHP&xid=cd9e84ec. Accessed 6 Dec. 2024.