Part 20 - Victoria Rice

Lisa Surridge and Mary Elizabeth Leighton argue that British and American readers would have had different experiences with the serialization of Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone due to the narrative effect of illustrations in the American publication (209). Installment 20, published in the British All The Year Round and the American Harper’s Weekly on May 6, 1868, accordingly offers a different experience to readers based on the serial they read. The installment is comprised of the first two chapters of the “Second Period: Second Narrative,” narrated by the lawyer, Mr. Bruff. Expanding upon Surridge and Leighton’s contention that the American publication garnered more sympathy for readers than its transatlantic counterpart, I will demonstrate how not only the illustrations, but the surrounding written works and paratext work together to influence readers’ reception of Bruff’s narrative. Bruff’s narrative serves the purpose of furthering the plot; Collins uses Bruff’s position as the family lawyer to provide exposition of the legal affairs. His status as a lawyer is meant to substantiate the information in his narrative. In each of the American and British publications, the paratext surrounding the chapters would inform the respective audiences’ understandings of the legal matters at play in the narrative. Below, I outline two examples of paratext from each of the publications that would contribute to contemporary readers’ understanding of legality in The Moonstone. The two excerpts of text from the volume of All The Year Round influence understanding of legality in The Moonstone through their negative framing of the legal system in England, whereas the two excerpts from Harper’s Weekly contribute to a positive framing of legality, particularly pertaining to individual interest. This project argues, through examining the paratext in the original serialization of Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone in both All The Year Round and Harper’s Weekly, that legality in the novel was understood differently between American and British audiences.

The above item, published in All The Year Round, is an excerpt from an anonymously published written work titled “Were They Guilty? Derived from a French Trial,” which centers around the murder of Louis Vilharden de Marcellange. The piece immediately follows the installment of The Moonstone in the issue, so British readers would likely read the pieces of text back-to-back. Simultaneously consuming two pieces of media that explore legality causes the reader to view them as two elements of the same narrative. As Leighton and Surridge suggest that illustrations “constitute plot elements” (210), so do accompanying articles and textual sources. The narrative in “Were they Guilty?” begins by detailing the marital struggles M. de Marcellange and his wife, Théodora, were experiencing. Théodora’s mother was a major influence in the couple’s struggles, as she went to the extent of asking the court for a separation of the couple. The author details the trial and sentencing of a servant for the murder of M. de Marcellange but implies that there may have been foul play by Théodora and her mother in the final line: “Were they the victims of circumstances? Or were they guilty?” (540). In The Moonstone, Rachel’s mother passes away and leaves behind a will that establishes Rachel to have “nothing but a life interest in the property” (Collins 261). Bruff’s narrative frames this as a form of protection for Rachel, and portrays Godfrey as money-hungry, as “it would be well worth his while to marry Miss Verinder for her income alone” (Collins 261). Yet, the content of “Were they Guilty?” may inspire deeper consideration of the circumstances of Rachel’s life-interest in the property. The characterization of Théodora and her mother portrays women as manipulative schemers; thus, readers might consider Rachel and her deceased mother in the same light.

Also appearing alongside The Moonstone in All The Year Round is a piece titled “Rich and Poor Bankrupts” by Malcolm Ronald Laing Meason. The piece is a condemnation of the difference in accessibility of the court system in England for rich and poor citizen bankruptcies. Meason gives example of his own experience navigating Bankruptcy Court, as well as relaying the experience of a foreman named Stevens with a sick wife and five children who was unable to pay his debts. His primary criticism is that creditors can effectively sentence their poorest debtors to jailtime under the current statutes, whereas richer debtors in the same position are granted a greater degree of mercy. Meason describes the proceedings in Bankruptcy Court as “bear-garden-like” (543). A bear garden was “an entertainment venue used for the baiting of bears and other animals” (“bear garden – noun”). To compare court to a bear garden implies predatory and inhumane practices. As established with “Were They Guilty?”, the inclusion of another piece that discusses legality inevitably interferes with the readers’ view of the legal system’s merits. Therefore, such characterization of Bankruptcy Court might prompt The Moonstone readers to question Mr. Bruff’s legitimacy as a narrator. Considering again the revelation in Bruff’s narrative of Rachel’s life-interest in the property, Meason’s characterization of the court system may frame Bruff’s involvement in executing the will as duplicitous. The apprehension readers may consequently develop towards Bruff contradicts Collins’ characterization of Bruff’s narrative as factual and trustworthy, thus altering reader experience with the novel.

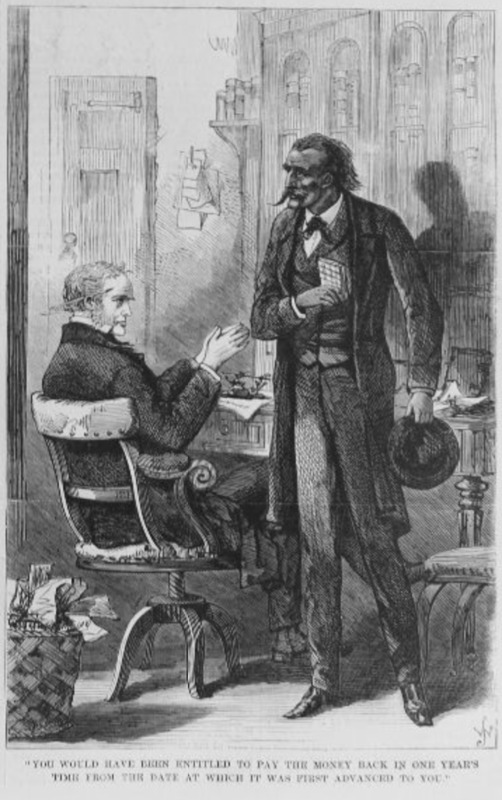

In the American publication Harper’s Weekly, installments of The Moonstone were accompanied by illustrations. Leighton and Surridge focus their analysis on the illustrations, arguing that the visual accompaniments “do not merely reflect or supplement the verbal text,” but instead “profoundly [affect] the narrative’s unfolding and meanings” (210). The illustration included with installment 20 of The Moonstone shows the moment when Mr. Bruff reveals to the Indian man who visits him that he “would have been entitled to pay the money back one year’s time from the date at which it was first advanced to [him]” (269). The illustration portrays the Indian man as well-dressed and almost assimilated into England. He stands with upright posture and there are no indications of deception in the portrayal. Bruff’s treatment of the man, when considered alongside the illustration, is no different than his common white man in England. Despite his fears, “If the Moonstone would have been in my possession, this Oriental gentleman would have murdered me, I am well aware,” Bruff does not appear visibly frightened by the Indian man in the illustration. The illustration appears proleptically, consequently priming the readers to view the text in accordance with the image, rather than the text serving as the primary source of understanding. As a result, readers will first understand Bruff as experiencing a calm, safe interaction with the Indian man, rather than a potentially dangerous exchange. This matters to the American readers’ understanding of legality in the novel because the illustration portrays the Indian man as a participating member of the legal system, perhaps even suggesting a contemporary debate around pursuit of individual interests under the law for racialized subjects. Without the inclusion of the illustration, readers are wholly reliant on Collins’ description to form notions about how racialized figures exist within the British legal system.

Unlike All The Year Round, Harper’s Weekly included a series of advertisements in their weekly publications. Having any advertisements at all changes the experience of reading The Moonstone, as they add contemporary social and economic context to the literature. Surridge and Leighton highlight how Collins sought out publishing opportunities that protected authorial interest (208). At the time of publication, cultural discourse over “a worry about the individual’s place within society” was developing and specific legal discourse regarding “authorial proprietary rights” was a foundation from which the mystery novel was developed (Bisla 178). In the May 16, 1868 publication of Harper’s Weekly, an advertisement for “Patent Offices,” offered by Munn & Company is included. Marketing counsel for inventors seeking patents, the advertisement is a related manifestation of cultural anxiety surrounding individual interest. Based on the inclusion of the advertisement, American readers of The Moonstone would have more context of developing ideas about ownership over intellectual property. Encouragement to seek out patent services could be viewed as no different than Godfrey accessing Mrs. Verinder’s will, or the Indian man inquiring about borrowing times. Each of these characters is depicted as self-interested and villainous in Bruff’s narrative, but a cultural focus on individual legal interest could skew the audience’s attitude towards support for Godfrey or the Indian man. Additionally, an advertisement for similar services to that which Bruff provides strengthens reader trust for Bruff’s narrative. Unlike the British audience, the American audience is likely to feel support for Bruff’s actions and opinions when considered alongside the paratext, because they are encouraged to seek out similar legal assistance to protect their own interest.

In conclusion, British and American experience with the paratext accompanying the serial print of The Moonstone differs significantly. As established, texts in the issue of All The Year Round with similar subject matter, but strongly negative themes are likely to influence the British audience’s attitude towards the legal system as it operates in The Moonstone. “Were They Guilty?” portrays women as suspicious, affecting the audience’s view of Rachel’s actions and Mrs. Verinder’s will. Similarly, Meason’s “Rich and Poor Bankrupts” depicts the legal system as inaccessible, particularly for lower classes, but instills a lack of confidence in the legal profession, thus undermining Bruff’s reliability among British audiences. Conversely, American audiences are likely to view legality in The Moonstone positively, due to the paratextual focus on individual interest. The illustration included provokes the audience to read the scene in accordance with the artist’s representation of the Indian man, as the image anticipates Collins’ description due to the placement in the publishing. Additionally, alongside The Moonstone in Harper’s Weekly is an advertisement that urges readers to seek out similar legal counsel to that offered in The Moonstone, reaffirming the focus on individual interest. Overall, this analysis advances Surridge and Leighton’s argument that the delivery of The Moonstone in the two print magazines results in contrasting experiences with the text on the two sides of the Atlantic.

Works Cited

“Bear Garden – Noun” Oxford English Dictionary, www.oed.com/dictionary/bear-garden_n?tab=factsheet#12795786300. Accessed 4 December 2024.

Bisla, Sundeep. “The Return of the Author: Privacy, Publication, the Mystery Novel, and The Moonstone.” Boundary 2, vol. 29, no. 1, 2002, pp. 177–222, doi.org/10.1215/01903659-29-1-177.

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. 1868. Oxford University Press, 2019.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. “The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper’s Weekly.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 42, no. 3, 2009, pp. 207–43, doi.org/10.1353/vpr.0.0083.